Any way you slice it, this fall is going to be hard on everyone and everything. Colleges are desperate for some tuition revenue, but we all know we are not offering the usual college experience. So far, most universities are planning some combination of

Fewer students on campus: some (like the University of Texas) are simply offering the option of taking remote classes only (but with no reduced tuition) while others (like Bowdoin College) are only letting first-years come to campus (along with a few senior honors thesis students and also, importantly, those who have home situations that make online learning nearly impossible.) Stanford is going to rotate students with half on campus for one quarter and then another half the next.

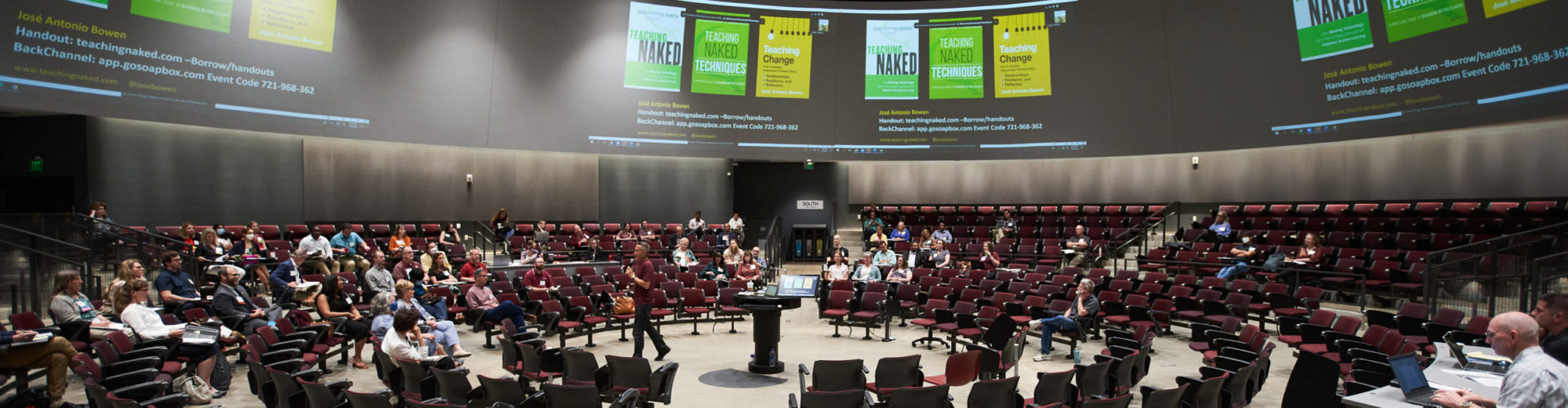

Fewer students in class: Many campuses have made all large classes online only and are reducing the capacity of rooms. Students spaced 6 feet apart and wearing masks has led to its own set of concerns about pedagogy: what active learning will work, for example. But recent analysis suggests that colleges are massively overestimating how many students they can safely have in spaces. A Cornell study found that colleges should be planning for only 13-24% of capacity. A CalTech study assumed 8 feet of distance—since longer proximity demands more distance and airflow is uncertain. They concluded (and did simulations with graphics you should see) that 11% was the maximum safe capacity, so only 16 students in a 149 seat 2000sf classroom!

Social isolation outside of class: students can expect singles, bathroom assignments, boxed meals and severe restrictions they won’t like. But in the words of the most recent academic mathematical models: “It is extremely important that students refrain from all contact outside of academic and residential settings.” The CalTech study also has dining hall simulations. It is summer and already the stories of transmission through social gathering has begun, but presidents seem to think most students will follow the rules when not being watched.

What this means for students is less incentive to come and if they do come (and pay with no refund option), the prospect of isolation and quarantine on top of a compromised education. For faculty this means some combination of virtual and F2F teaching (i.e. more work) and preparation even in small classes for some students in quarantine and online for part of the semester. I’ve already suggested that virtual and F2F are not easily done together and simultaneously; spending money on webcams and screens in every classroom is unlikely to improve the quality of instruction or any feeling of engagement. Below are alternative ideas.

Part of the problem is that we always want to replicate rather than innovate. Forget about the past. This disruption is real and massive. It is time to look at some wilder ideas—even some beyond the 15 scenarios Joshua Kim and Edward Maloney have proposed—although some of these are updates of those. I will look first at the institutional level and in the next blog at things individual teachers can do. Before you say no, consider the following:

(1) What you are currently considering is already a lot of extra work, motivated by a potential budgetary collapse, unappealing to almost everyone, could fail terribly, and will increase inequity. Relationships are fundamental to good education, especially when cognitive bandwidth is compromised through stress and uncertainty, so our goal should be to maximize faculty time and ability for supporting students. Asking faculty to redesign all courses for a complicated set of technical specifications (simultaneous F2F and virtual) does not play to our strengths.

(2) Really big ideas are iterative. None of these are fully baked and all will need adaptation to your campus and your students. Many could be combined and maybe only a piece of something works for you. You are already planning on spending tremendous amounts of effort and money to replicate very poorly what you offered last fall.

(3) Yes, these might fail, but everything we are trying comes with risk. Which is most likely to prepare your institution for success this fall and in a few years? Try asking “how might we make this work?” first and generate a few more detailed alternatives for your campus, and then decide which two or three to pursue in greater detail.

(4) Yes, time is short, but the situation is also changing quickly: what will you do if your state demands a 2-week quarantine for students coming from California, Arizona, Texas or Florida? Is your campus already reporting COVID cases in staff and students? Now is the time to start generating more options.

1. Family-Style Quarantined Residential Learning Communities

In many neighborhoods, groups are families are deciding they can cooperate and quarantine together: after two weeks of individual quarantine they remove the social barriers between their households and act like one extended family. Similarly, small (20-50-100?) groups of faculty, staff and students could live together people in isolated clusters for a few weeks or an entire semester, WITHOUT social distancing (after testing or a short quarantine). Think of this like one of the 38 Oxford colleges—an isolated social and educational unit as part of a larger university. Students might need to isolate in dorm units, but faculty could quarantine at home as the recent SpaceX astronauts did. That is a serious adjustment, but with serious benefits too. (Many people who work as first responders or hospital workers have spent months without hugging their own children.)

Within this unit there would be no need for low density. Students could eat, sleep, party and have sex together. (Some older dorms have their own dining halls, but a housing unit could also eat in its own group shift in the main dining hall without restrictions.) Even double rooms (with some reserved singles for quarantine perhaps) might be fine. Faculty who were willing and able to live in the dorm might teach a double load for a semester (or perhaps a shorter block within the semester of 4 or 8 weeks) and then be off the next block. (They would have to pledge to self-isolate when away from the campus to be most safe.)

Each “family-style” learning community would operate a little like an individual isolated college. As is the case at Oxford and Cambridge, individual colleges would have limited subjects and faculty, but students can take (virtual in this case) courses from any other part of the university. But this way, (1) they get some of the other social benefits of college and (2) some great F2F classes.

Since this is a temporary situation, students could join different cohorts of subjects in different semesters (since all of this is probably going to be in place for spring as well). The first-year STEM kids mostly take the same 3-4 courses anyway—maybe they lose the choice of an English topic, but they get to come to campus and have some college life. Or they take a couple of core subjects together in the dorm/college and then take an elective online. Most universities are already planning a lot of online only courses.

The advantages would include almost full capacity and full revenue. You no longer need low density. You have to social distance when you leave your dorm or hall, but you get to party within your cohort. If the entire campus is isolated in this way, then after two weeks larger groups could be allowed to mix—depending on the risk you want to take.

This model would also work for graduate students in the same program. The incoming cohort of physics or history PhDs will take some group of courses together anyway. Many of us lived together or in isolation in grad school and building a cohort might even increase retention and a sense of community.

2. Cohorts and Streamlining Curriculum

Cohorts would be less radical and less effective at slowing viral spread. Cohorts are underutilized because we are so fond of choice—everyone wants a unique English class at the time they want it and faculty want the freedom to design classes with individual approaches. All good things, but reducing some content choice will allow for more and better teaching options this fall. Streamlining the curriculum could allow a larger group of students to work together and support each other through a series of courses. This works best for first-year students, where cohorts are already most common, but would also work for big problem interdisciplinary courses (see below).

First, it makes it easier to schedule students and reduces some of the inherent infection problems that campuses will have. Even with small classes, if students are with a different group of 20 students every hour, an infection can still be spread rapidly. A cohort moving from class to class together reduces this risk. Cohorts also create community and shared experiences.

Even if the same students are not simply moving from class to class together, streamlining has other benefits. If sections that meet in the same week are more interchangeable (i.e. they present the same activity about the same content) then students still have choice of times and format, and online and F2F groups can be separated. Students can easily move from quarantine to physical class and back again. Second, compromising a little on individual approach (where every section taught by an individual faculty member varies dramatically from every other presentation of the same material) means that work can be shared. During the current crisis, many of these benefits are magnified and perhaps begin to outweigh the other compromises being made.

3. Big Problem Interdisciplinary Seminars

Offering a couple of larger interdisciplinary courses would create engagement, relevance and focus, allow for small group projects and experiences, and build community through shared experiences for students. It would allow for higher quality shared asynchronous video content (if individual faculty are recording only a few lecture videos a semester, they can be really good and not everyone would have to or would want to do what is a highly specialized skill) combined with synchronous small group high-touch faculty and student interactions. This is work that can be divided and shared. Not everyone has to design and teach every part of the course. At a time when work has annihilated summer research, perhaps we are ready for more collaborative efficiency. (I’ve already written about teaching pandemic courses and combining sections of large classes, what I call the HyFlex Flip.) Most campuses already has some structure for this.

Take this to scale and imagine every student on campus taking one of three or four big ideas courses (or even just one big course on the pandemic). Weekly sections could involve giant jigsaw projects and individual faculty could still supervise small groups doing individual projects. This would significantly ease the complexity of the schedule (especially with the need for more time between classes and over-capacity rooms, but mostly for trying to accommodate all of the usual choice in time and format of courses.)

Our students need community and engagement more than ever and faculty need some relief from the endless permutations of planning now being done.

This could also be done virtually—in fact most of the planning for this fall was done this way—in large interdisciplinary committees. Many of us have now attended a virtual conference and students routinely use social media and other virtual tools to think about how to solve large social problems.

4. Focus on Racial Equity

Has your campus issued a statement about how deeply you care about racial equity? There is a topic for one of your large interdisciplinary seminars. There will be plenty of naysayers who say that chemistry or engineering is immune from this, but what would happen if you really looked at the potential for how everyone feels in these classes? Are there really no women or scientists of color that could be discussed? Why are certain diseases and projects funded? Who benefits? How might science be done more equitably? Again, not everyone has to design an entire semester of material, but could you change your campus culture and curriculum going forward if the science faculty focused on two weeks of content but spent the rest of the semester involved in this collaborative exploration and working with students to understand the issues? I challenge you to think of a more important or transformative project for your campus.

You could go even further and create a single campus seminar or focus virtually all of the fall curriculum on race and equity for your campus. You would probably still want to offer a few other required courses for majors, but could you design a large (say 3, 6 or 9 credit) course for everyone that would focus on a problem that virtually everyone thinks matters right now? Groups of biology or history majors could work on their own projects, but there would be a bold campus commitment to something that is engaging and important. What about how to do campus policing and public safety more equitably? This could also be the focus of a new gap year program (see below).

5. Some Students in Residence, Most Classes Virtual.

Before we understood quite how reduced residential capacity was going to be, Joshua Kim and Edward Maloney proposed all students in residence but learning virtually. Capacity will be reduced further now because everyone wants a single, but that is still some residential revenue and one predominate delivery method of instruction is easier to deliver well. If faculty know now they are going to be teaching online (and circumstances might still force everyone into this mode) they can prepare better courses. We are also already seeing that many faculty will not be able or willing to teach F2F, and as cases and quarantines multiply in the fall, that number will grow. Plan now for better instruction and take advantage of the asynchronous potential of real online teaching.

With some students in residence, there is also the option to hold some small F2F sessions, and some separate but synchronous virtual classes. Combine this with some of the potential of idea no 1 above. Relieved of trying to do the impossible—simultaneous virtual and F2F—faculty can prepare better online courses and some can still deliver the high touch relationships of a physical campus. Faculty can still meet individually or in small groups with students in dorms or offices (although my suggestion in any case is that F2F office hours be moved to unused classrooms or other large spaces with excellent ventilation and good coffee) and separate sessions for virtual students.

6. Structured Gap Year

Gap years (and structured group internships have been growing in popularity and often result in students who return to campus with more focus and maturity. It was fourth in the InsideHigherEd survey of what appealed to students for Fall 2020 and should get more attention.

Gap years struggle at the concept level because we think of them as lots of individual events without a revenue stream, but if colleges design them, both problems can be eliminated. Could you charge students (a small amount) and then hire them out to do work for someone else? Yes, if you really provide value and structure—and if you price it right, federal aid might cover it. Further, you might also be able to house them while they do work in your local community. This won’t solve the density problem, but for many campuses under-enrollment may be the problem.

Start with meaningful projects that exist on your campus. Do you need to rethink environmental sustainability or the history of racial injustice on your land? For many campuses there will be a pressing need to re-evaluate what services are necessary and affordable? Could you rethink work study? Streamline support? Could students form a co-op to grow food? (I spent 2 years in college in a co-op where we cooked all of our own food and had no university cleaning service; a mess, but a happy mess.) Is there a massive digitization project that needs to occur? More broadly could students now become a major factor in redesigning your institution to survive? Northeastern has made co-op programs and experiential learning a central part of their experience and you can learn from them.

You could equally start with the needs of your local community. There are surely hundreds of projects that could benefit both your town and the town gown relationships. Do you have a feeder campus with a few students waiting to transfer? Do you have an alum who lives near them? Start with a set of meaningful projects and then integrate with existing curriculum and grant some credits that will generate revenue. With the maximum Pell grants for 2020-21 set at $6,345, $7000 for 6 credits plus room and board might create some revenue and still provide access to transformative work.

7. Virtual Structured Gap Year

If keeping students away but engaged is the goal, then a gap year might need to be virtual. Champlain College is charging about a third of its $21,000 tuition for a 6-credit Virtual Gap Program described as “a semester-long, inspiring journey into academic college life, holistic well-being, and finding meaning through virtual internship and service experiences.” The Global Citizen Academy offers leadership training and usually a global fellowship, but this year it will be virtual.

Thanks to the internet, the ability to form a global network and have real conversations with people on the ground in different countries is much easier—easier than it is to visit. Faculty already have connections around the globe; perhaps those connections could be used to create some student projects. Work, yes, but perhaps less work than the current redesigning of courses.

There are also thousands of new local Covid-19 problems (to add to all of the existing ones). Could you combine some existing data-analytics course, leadership, sociology or public-policy course with a problem that most local communities might be facing and let students do work in their own communities for a year? Or perhaps you outsource that to the local community college and offer the other 3-credits of structured gap year internship/work.

Note that there is already gap year competition from institutions that accel at online education. Park University, for example, is offering a flat fee ($9000) virtual “gap year tuition” that is really just a clever marketing ploy. It is not a gap year program, but with years of offering online degrees, student could reasonably anticipate that a year at Park, or Western Governors University or Southern New Hampshire might deliver better courses at a lower price point. Outlier and the University of Pittsburgh are offering asynchronous transferable courses (Calculus and Intro to Psych so far) with tutoring and study groups for $400 for 3 credits (refunded if you do the work but do not get a passing grade!) All institutions, will certainly make transferring credits back to you sound easier than it is, but if a virtual experience at a lower price delivers higher quality instruction than you do, students may just transfer. As ToysRus and other have discovered, there is more competition online. Here is an opportunity to design a different sort of transformative college experience, but you have to think beyond just “courses.” With the barrier to online education lowered, your price point is about to come under attack. Now is the time to look for a compromise, even if it means looking at the sacred cow of “only we can teach that.”

8. Virtual (and Global) Partners

While classroom discussion and relationships are virtual, perhaps now is the time to find a partner university, organization or even corporation somewhere far away. This could be a simple virtual exchange program—with professors swapping teaching assignments in another country. More complicated but better would be to take the virtual classrooms that you are already creating and use this opportunity to create much more diverse classrooms. Most campuses suffer from some problematic homogeneity in classroom discussions—students are from similar places, backgrounds or academic orientations. That is being replicated in virtual classrooms, the world awaits online.

Normally we think of local when we look for partnerships or consortium, and there is a benefit in sharing services, academic support or course design with another institution. But with more classes going virtual, you could pick a partner institution or two that has a complementary mission, but is across the state, country or planet. If your student population is too homogeneous, find an institution that has different students. Partner with an HBCU an HSI or an institution that serves a different region, age or demographic. That will indeed create new problems, but it might also increase learning.

The Stevens Initiative of the Aspen Institute has resources (and even grants!) to help you set up something. It might just be a single project, like the COVID-19 Virtual Global Design Challenge that the Johns Hopkins University Center for Bioengineering Innovation and Design created this spring (with over 200 teams) or IREX’s Global Solutions Sustainability Challenge, which uses a project-based learning model. You could look to share a course and create more diverse discussion groups or find a partner institution that already uses your LMS—although with Zoom as a common format for so many classes, this is much easier lift than you imagine. There are lots of English-speaking students at Indian universities, and India also has a growing number of new liberal arts universities and a shortage of faculty.

Maybe you could partner with an institution that has more online experience then you do? Many of them serve more older or active-duty military populations. Once again, if some faculty were willing to use some existing designed for online content and focus on leading small group discussions, then your (usually higher) student tuition might present a good partnership opportunity: your faculty teach and assess for the credits you will award, but classes are mixed. Again, some financial potential and a better use of faculty time, but also maybe better learning.

Even more widely, is there an organization somewhere where your students might add a GenZ perspective? Is there a country or corporation that a faculty member is already working with? If we say we are preparing students to work in a global world, maybe they can start now.

9. Real Tutorials

Joshua Kim and Edward Maloney have already outlined some ways that American universities might “modify the Oxbridge tutorial model. As they point out, small group meetings could be combined with lots of other ideas and I have combined it with flipping in my HyFlexFlip. Here is a more radical idea—one also closer to the Oxbridge model.

Many residential colleges have a 20/1 or even 15/1 or lower student/faculty ratio. Suppose that instead of redesigning all of our courses, that we used the incredible breadth of free courses that already exist from Courera, EdX, OpenYale, CrashCourse, Khan Academy, Open Culture, Merlot, Carnegie Mellon Open Learning or YouTube and took the tutorial model seriously. Faculty would meet with all 15 or 20 students every week (either virtually or F2F as available) or in small groups of 3 or 4 when subjects overlapped. As with the 1-1 Oxford tutorials or the University of Cambridge small group supervisions, this works best when student and teacher share interests, but relationships lie at the heart of the approach. No tutor will know all of the subjects a student will want to study—that is why there are also optional lectures—in this case free online lectures and entire courses. The tutor provides accountability and supervision, helping the student decide which content might be most useful

Faculty could still provide lectures and content they thought was needed, but this really only works at scale if we use existing textbooks and online videos as content. Once we make this leap, we can then focus on learning, support, assessment and awarding credits. This combines with many of the previous ideas.

10. Relationship-First Hybrids

One common model for hybrid distance graduate programs is to start by bringing people together first; these are sometimes called low-residency programs. The key is that they usually START with a residency, perhaps a week or two when people get to know each other. As has been noted about this spring: relationships already formed in person are easier to continue online. Low-residency programs were designed to allow an international group to come together, become friends and then leave, but still learn together while dispersed all over the world. During a time of travel restrictions that won’t work, but the idea might be adapted to our need to limit physical interactions, even if we live near each other.

Could we meet students where they are—literally. You already know where your students live. This might be in which cities if you are a national institution or in which neighborhoods if you are local. One version of this would be simply to create neighborhood or local “cohorts” of students who could get together physically to create some relational bonds. Let students know who is already around them at your institution.

To create true relationship-first hybrid courses (probably mostly for regional institutions, but think also about your feeder schools), students would get together initially in groups physically with the professor. This would require social distancing, but at least being together physically, even for just a day, does create a sense of connection. You could use your largest spaces and rotate who comes when. For commuter campuses or community colleges this could massively change the engagement and perception of support. For the first day of class (and perhaps once every two weeks or once a month after that) groups come together physically and then spend the rest of the time online. Online groups can create a similar sense of community, but for those of us who teach mostly F2F, this might be a safe and easy way to simulate the positive feelings of community that we took into our online transition.

Transition Now toward the Growing Market

A crisis always shifts short-term attention to the tactical, or “business continuity” or how we keep doing what we were doing. But strategy is about what will improve our odds for the future. You have been told for years now that a huge demographic shift is coming. Covid-19 will only accelerate your need to shift in that direction.

A new survey finds that with massive potential job losses, 35% of Americans say they would change FIELD if they lost their job, but only 44% say they have access to the education they need. A quarter of all Americans say they are planning to enroll in some sort of training or education in the next six months, but most (62%) say they want skills training and not a degree. 46% want that training online. Add to that the Trump administration plan to focus federal hiring on skills and not degrees (and campaign that others do the same) and the public sense (however mistaken) that a tradition college degree is not worth the expense, is likely to grow. This may not be the market you want, but it is the market you now have.

In other words, Covid-19 presents a crisis that is not likely to be only short-term for most colleges. It will accelerate some trends and generate its own set of new behaviors. Restaurants, the arts and the airlines are starting to think about what happens as behaviors change. Consider that few would question the value or quality of a Broadway show, but would you be willing to go? There will finally be tickets to Hamilton in 2021, but are you sure you want to invest money in a trip now or just stream it from Disney Plus? For years movie theaters have survived against VCRs and now streaming services, but they might not survive this pandemic.

Now, for example, is an important time to ask: which of our courses and degree programs can really only be taught F2F or residentially, and which might now be moved, and even improved, online? That does not mean the end of residential education: the value of community has only be affirmed by the pandemic. But we have also learned that some working from home can be more productive and that well-designed online learning can be effective. You have new data, market conditions, assumptions and behaviors. Use them.

Market share tends to shift more dramatically during volatile times and higher education will not be immune. Your planning time for fall is short, but at least some portion of your time and some collective group on your campus needs to be thinking wildly outside of the box right now. You need options. You need also the be thinking strategically about the bigger “what if” scenarios and the “how might we” questions. Try a pilot program of something, anything, new this fall—just in case your attempts to recreate Fall 2019 fail. Strategy is the art of sacrifice. What do you need to be considering for this fall that can also improve your odds for success years from now?

NEXT: Individual strategies for faculty planning for simultaneous virtual and social distanced classrooms.